This year marks the hundredth anniversary of the Bauhaus, arguably the 20th century’s most influential college of art, architecture and design. Officially founded on 1 April 1919 by German-born architect Walter Gropius, the Bauhaus was a revolutionary new establishment. With the intention to rethink design from the bottom-up, the school’s objective was to reunite fine art and functional design—its focus was very much on shaping the modern age, creating everyday objects that could be manufactured in collaboration with industry. The Bauhaus and its artistic avant-garde had lofty ambitions. Their desire was to conceive and create the ‘new building of the future’, combining the separate disciplines of architecture, sculpture and painting in one single form: it was truly a modern philosophy of design.

The Bauhaus Building in Dessau. Image © Bauhaus Dessau Foundation.

Marianne Brandt. Image via Chamber.

Despite a claim by Walter Gropius that the Bauhaus would embrace equality, women were in fact marginalised. His stated intention that there ‘should be no difference between the beautiful and the strong sex’, actually betrayed his true feelings. The most famous Bauhaus masters and grandees were predominantly men, including: Gropius (the school’s first director), Marcel Breuer, Vassily Kandinsky, Josef Albers, Hannes Meyer (the school’s second director) and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (its third director). There was a concern that too many women would undermine the Bauhaus’s credibility and so Gropius placed a quota on the number of female applicants. Moreover, women were directed towards subjects deemed feminine in nature, such as weaving and pottery. The metals workshop, for instance, was considered a masculine domain. In the Bauhaus’s fourteen years, only eleven women managed to find a way round its gender restrictions: one of those women, Marianne Brandt, was arguably its most successful student.

Marianne Brandt, Untitled (Self Portrait with Jewelry [sic] for the Metal Party), 1929. Image via Core77.

Model No. MT 49 teapot (1924). Image © 2019 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. An authentic Model No. MT 49 teapot is a highly valued object. On 14 December 2007, an original MT 49 teapot was sold for $361,000 to a private American museum during an auction at Sotheby’s, New York. Source: Dezeen.

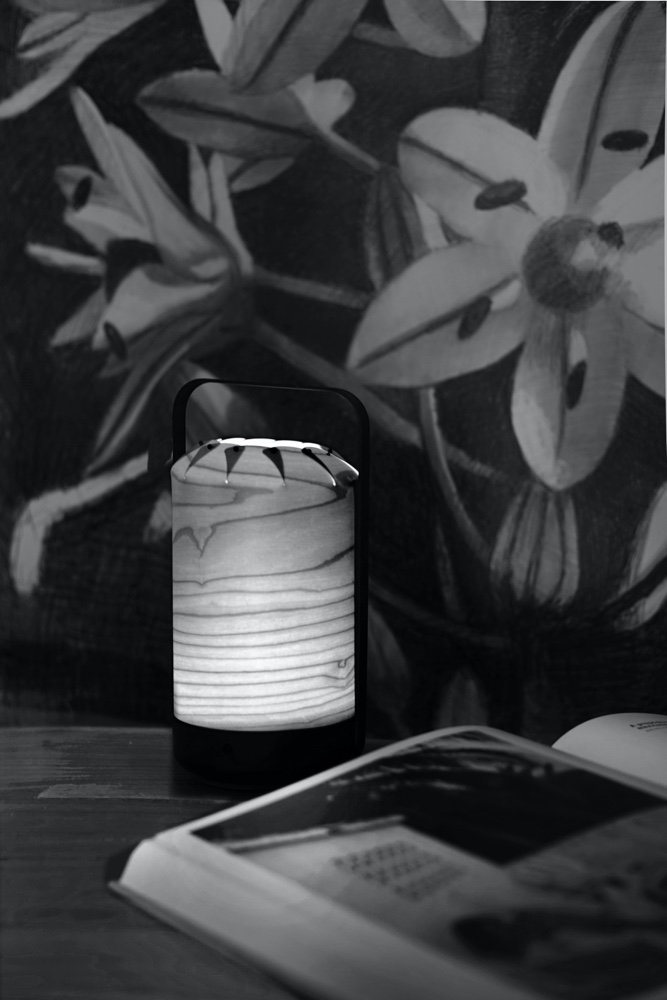

In 1924, Brandt designed the Model No. MT 49 teapot, one of her earliest and most famous projects. Although conceived as an object for industrial manufacturing, with its hammered silver body and ebony handles, it was unsuitable. However, the teapot was an artistic marvel: at just seven centimetres tall and designed with an asymmetrical lid to reduce drips, the teapot brewed a concentrated tea extract. The Model No. MT 49 teapot has been described as ‘Bauhaus in a nutshell’, with its industrial design aesthetic and an emphasis on functionality. Brandt would design a number of the Bauhaus’s most iconic objects, including an ashtray resembling a metal sphere cut in half and the best-selling modernist Kandem lamp.

Kandem table lamp (1928). Image via Chamber.

Kandem Bedside Table Lamp (1928). Image © 2019 The Museum of Modern Art.

This Marianne Brandt ashtray (designed in 1924) combines a classic Bauhaus-style combination of basic geometric shapes. It is produced under license by Alessi. Image © 2019 ALESSI S.P.A.

Marianne Brandt left the Bauhaus in 1929, temporarily joining Walter Gropius (who had left the school in 1928) at his Berlin-based architecture practice. In 1930, she was appointed head of design at the Ruppelwerk Metallwarenfabrik (Metal Products Factory) in Gotha, Germany. Despite struggling to win the respect of the factory’s male technicians and dealing with Ruppelwerk’s more conservative aspirations, Brandt remained as head of design for three years. But an economic depression and the constraints of the Third Reich following its seizure of power, meant her position was untenable and she had to leave Ruppelwerk.

Table clock by Marianne Brandt, with painted and chrome-plated metal. Manufactured by Ruppelwerk GmbH in 1930. Image via Wright.

The Bauhaus was active for just fourteen years—from 1919–1933—and enjoyed its heyday at the Bauhaus Dessau site (1925–1932). With its comprehensive approach to modernity and progressive thinking, the school’s dissolution was inevitable: Nazi repression and draconian cutbacks in funding ensured its demise. Subsequent to its closure, many of those who taught and studied at the Bauhaus moved across Europe and emigrated to the USA, where they would disseminate the school’s liberal ideas and concepts.

For Brandt, she chose to live at her family home in Chemnitz, eastern Germany. Following WWII, with her modern, forward-thinking ideas, Brandt was subject to the Zhdanov Doctrine: a cultural policy of the Soviet Union that called for the strict control of art and intellectual activity, and the promotion of an anti-Western bias. Brandt did work as a teacher of design, with positions at the HfBK Dresden and Berlin Weißensee School of Art. She was also a painter and a pioneering photographer, working on still-life compositions and striking self-portraits.

Marianne Brandt self-portrait. Image via House Theory.

It wasn’t until the 1970s that Marianne Brandt’s metalwork and photography began to receive critical attention, by which time she was in her eighties. Today, her ashtray, teapot, lamp designs and designs for other household objects are recognised as some of the best examples of modern design to emerge from the Bauhaus. Perhaps most notable was her pioneering spirit and attitude, and in particular her successful accomplishments in what was, at the time, a male dominated field of design. It begs the question, was the Bauhaus a bastion of male chauvinism?

Bibliography

Bauhaus100.com. (2019). Marianne Brandt. [online] Available at: https://www.bauhaus100.com/the-bauhaus/people/masters-and-teachers/marianne-brandt/ [Accessed 7 Mar. 2019].

Bauhaus.de. (2019). Bauhaus-Archiv | Museum für Gestaltung, Berlin. [online] Available at: https://www.bauhaus.de/en/ [Accessed 7 Mar. 2019].

Bauhaus-dessau.de. (2019). Bauhaus Dessau. [online] Available at: https://www.bauhaus-dessau.de/en/index.html [Accessed 7 Mar. 2019].

Sellers, L. (2017). Women design. 1st ed. London: Frances Lincoln.