Unlike Charles and Ray Eames, the design duo name ‘Alvar and Aino Aalto’ does not roll so easily off the tongue or feel particularly familiar. This is because Alvar is very much the foremost Aalto, his wife Aino taking a distant second place in the annals of design history (and that is not to say that Ray wasn’t overshadowed by Charles—she certainly was). However, design discourse has arguably been much kinder to the Eameses as a prolific duo, whereas Aalto is synonymous with the genius of Alvar.

A 1940s photo of Aino Aalto. Photo by Kolmio © Artek.

Aino Marsio–Aalto (1894–1949) was both an architect and designer, having studied architecture at the progressive Helsinki Institute of Technology (now part of the Aalto University—named as an ‘homage to the life and work of architect Alvar Aalto’, according to the University’s website). In point of fact, plans for the (now) Aalto University Otaniemi campus were drawn up by both Alvar and Aino. In her book ‘Women Design’, author and design historian Libby Sellers points to a reassessment of Aino Aalto’s legacy as a product of our times and, perhaps more importantly, ‘an overdue re-evaluation of a patriarchal history of modernism.’ (Sellers, 2017) Sellers notes that, like many design partnerships (such as the Eameses), the Aaltos would usually sign projects to the company and not to the individual, making it difficult to work out the actual division of creative attribution (although history does favour Alvar).

A 1940s photo of Aino and Alvar Aalto. Photo by Herbert Matter © Artek.

Alvar and Aino met at the Helsinki Institute of Technology. After graduating in 1920, Aino worked for a period with the Finnish architect Oiva Kallio in Helsinki and later the architect Gunnar A. Wahlroos, before joining Alvar Aalto’s burgeoning practice in 1924. Within six months they were married and a formidable design partnership was forged. The pair would travel often throughout Europe, forming alliances and friendships with notable members of the European avant-garde: French architect Le Corbusier, German-born architect and Bauhaus director Walter Gropius, and the Hungarian constructivist artist László Moholy-Nagy, to name a few. When they returned to Finland, the Aaltos established a joint office, bringing together those ideas learned from their European counterparts with a particular Finnish design perspective. Believing in the idea of ‘design for everyday life’, Alvar and Aino would collaborate on many projects during the 1920s and 1930s, designing everything from the architecture to the furniture, fixtures and fittings. Famous examples include the Paimio Sanatorium, Villa Mairea, the Viipuri Library and the Savoy Restaurant in Helsinki. Aino’s strong moral compass—doubtless informed by a liberal childhood and growing up in the first cooperative apartment building in Helsinki—meant that she often favoured social projects.

In 1929, the Aaltos won an open competition to design the 184-bed Paimio Sanatorium (later renamed the Paimio Hospital): an isolation hospital for patients with tuberculosis, it’s located around 30 km east of Turku in SW Finland. Built between 1930 and 1933, the functional yet humane design capitalised on the surrounding nature and focused attention on the needs of patients. Much thought was given to the environmental design, including the need for sunlight and fresh air, as well as comfort, lighting and furniture.

The Paimio Sanatorium’s exterior facade. Photo © Pieter Lozie.

Light enters the sanatorium’s library through its expansive windows. Furniture and lighting were designed by Aino and Alvar Aalto. Photo © Finnish Design Shop.

An interior space in the Paimio Sanatorium. Photo © Pieter Lozie.

Villa Mairea was a modern residence designed by the Aaltos for Maire and Harry Gullichsen, both art aficionados. Built in 1939, the home achieved world-wide attention and acclaim, combining Alvar Aalto’s organic forms with Aino Aalto’s modern interior.

Villa Mairea’s exterior view. Photo © Åke E:son Lindman via ArchEyes.

The interior living space at Villa Mairea. Photo © Åke E:son Lindman via ArchEyes.

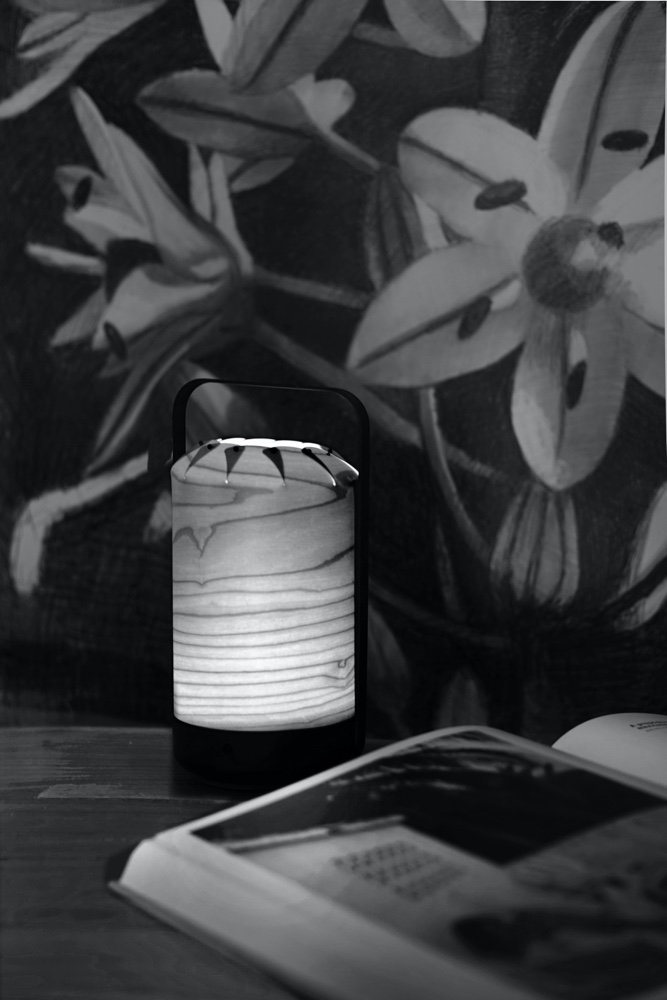

Although known for her work in glass (especially her ‘Aalto Glasses’ manufactured by iconic Finnish brand Iittala), interiors and furniture design, Aino had a keen interest in architecture, photography and applied art. She was also a savvy businesswoman and her punctilious nature was said to balance Alvar’s more spontaneous, bohemian character. As such, Aino was core to the development and ultimate success of Artek (whose name is a synthesis of ‘art’ and ‘technology’).

Aino Aalto’s ‘Aalto Glasses’ won the gold medal at the 1936 Milan Triennial. The glasses were were inspired by the circles created when throwing rocks into water. Photo © Fiskars Finland.

Founded in 1935 by Alvar and Aino Aalto, Maire Gullichsen (Finnish art collector, curator and later resident of Villa Mairea), and Nils-Gustav Hahl (an art historian), Artek’s manifest was in essence ‘to achieve a synthesis of the arts, improve everyday living, and bring modernism to Finland [and indeed beyond].’ (Artek, 2019) The company would encourage an aesthetic lifestyle at home, with designs that were both beautiful and functional—a principle that Artek maintains today.

The Artek factory in 1936. Photo © Artek.

The first Artek store in Helsinki, 1936. Photo © Artek.

For Aino’s part, in addition to her own projects and collaborations with Alvar, she was Artek’s first Design Director and from 1941, its Managing Director. Aino’s leadership was essential to determining Artek’s aesthetic direction and her input would help realise the objectives laid out in the 1935 Artek Manifest. Under Aino’s direction, Artek’s worldwide roster of clients would grow, yet it was the Aaltos’ own architecture practice that was the company’s biggest client. With Alvar’s predominance as an architect, Artek was increasingly linked with him—ergo, Aino’s key contributions to the company were absorbed as part of its legacy and rarely differentiated.

Aino Aalto’s organic Riihitie Plant Pot for Artek was originally designed in 1937 for the terrace of the home she and Alvar built on Helsinki’s Riihitie Road. Photo by Carl Kleine © Artek.

Aino Aalto’s 1932 Side Table 606 is made up of a tubular steel frame and a birch plywood top. It was originally used as a stool for changing shoes. Photo © Artek.

Sadly, Aino’s untimely death in 1949 is likely to have contributed to her relative design anonymity. And yet Artek is doubtless her greatest achievement, her determined efforts, aesthetic vision and creative prowess building the foundation on which the company has today flourished. Aino Aalto must certainly be applauded for her part in ensuring that Artek maintains an important place in modern design discourse.

Bibliography

Aalto.fi. (2018). History | Aalto University. [online] Available at: https://www.aalto.fi/aalto-university/history [Accessed 25 Apr. 2019].

Artek. (2019). Artek – About Artek. [online] Available at: https://www.artek.fi/en/company/about [Accessed 25 Apr. 2019].

Artek. (2019). Artek – Aino Aalto. [online] Available at: https://www.artek.fi/en/company/designers/aino-aalto [Accessed 25 Apr. 2019].

Sellers, L. (2017). Women design. 1st ed. London: Frances Lincoln.