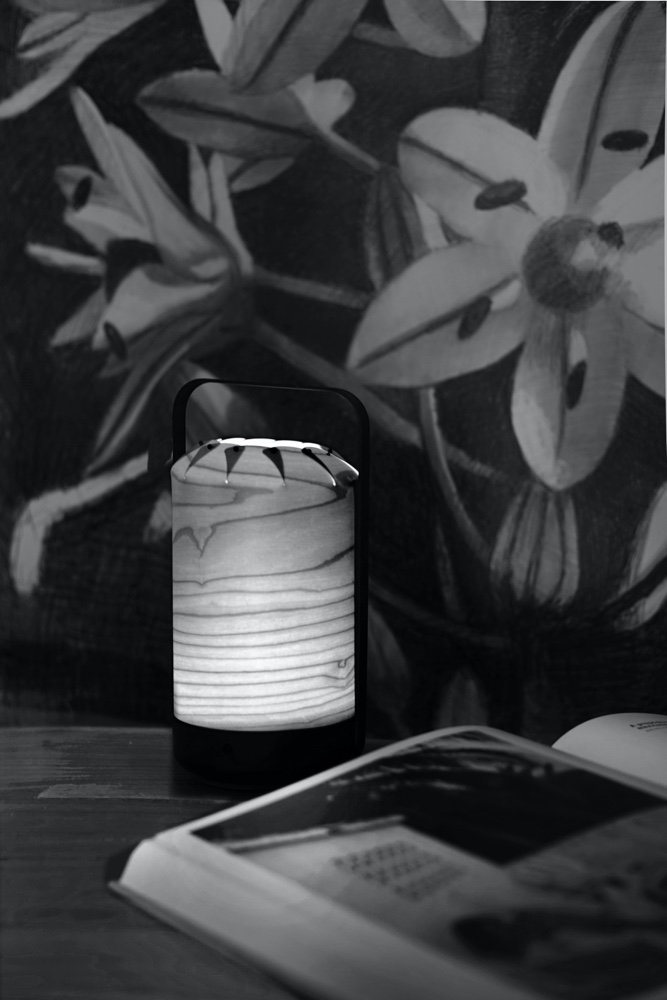

In this new monthly series, LZF considers the often overlooked and undervalued contribution of women in design.

When we reflect on the great architects and designers of the twentieth century, we usually think about men: Le Corbusier, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Charles Eames, Alvar Aalto, Hans J. Wegner, Arne Jacobsen and Eero Saarinen, to name but a few. And yet, not to deny the contribution of these truly remarkable pioneers of design, women, as a consequence, are frequently overlooked. Celebrated twentieth century female visionaries, women such as Ray Eames, Charlotte Perriand, Eileen Gray, Greta Magnusson-Grossman, Aino Aalto and Anna Castelli Ferrieri, have contributed much to the annals of modern design. And sadly, on 25th January 2019 the world lost Florence Knoll Bassett, one of the last remaining design legends of the twentieth century. She was 101.

Florence Knoll Bassett in 1961. Ray Fisher/The LIFE Images Collection, via Getty Images.

Of Florence Knoll, Charles Eames once proclaimed: ‘Each time I go East I see something you have done… [i]t is always good, and I feel grateful to you for doing such work in a world where mediocrity is the norm.’ (An excerpt from a letter that Charles Eames wrote to Florence Knoll in 1957: Source). Both Eames and Knoll were fellow classmates at the Cranbrook Academy of Art in Michigan and during her long life, Florence Knoll certainly represented the antithesis of mediocrity. Born in Michigan in 1917, Florence Schust (her maiden name) was left an orphan at just twelve years old. As a young girl, she demonstrated a keen interest in architecture and was enrolled at the Kingswood School for girls, adjacent to the Cranbrook Academy of Art. Here, Florence met the Finnish architect Eliel Saarinen (he had immigrated to the US in 1923, and later designed the Cranbrook Academy of Art and Kingswood School for girls, as well as other buildings on the campus). She was warmly welcomed by the Saarinen family, vacationing with them on occasion in Finland, and formed a close bond with Eliel’s son, Eero (whom she would later work with at Knoll).

Florence Knoll and Eero Saarinen in 1957, studying the Tulip base. Courtesy of Knoll, Inc.

Florence studied under Eliel Saarinen at Cranbrook, burgeoning and later flourishing as a student of design. In a who’s who of influential twentieth century design names, she was also a protégée of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer. Walter Gropius had set up the Bauhaus in 1919, a revolutionary establishment that worked to unify the separate disciplines of art and craft, bringing them under one roof to achieve novel and contemporary forms of architecture and design. This approach very much influenced Florence Knoll and she engaged with modernism throughout her career, amalgamating architecture, art and function in her furniture designs and interiors.

New York Times article. Courtesy of Knoll, Inc.

Moving to New York in 1941, Florence met Hans Knoll, who was at that time setting up his own furniture company: Knoll. With her remarkable design prowess and Hans’s shrewd business sense, they made a prodigious team, growing Knoll into an internationally renowned design authority. The two married in 1946 (tragically, Hans Knoll died in a car accident in 1955—Florence subsequently married Harry Hood Bassett, a Miami banker, in 1958, adopting the name Florence Knoll Bassett). After Hans’s untimely death, Florence assumed the role of president at Knoll (though she did sell the company to the Art Metal Construction Company in 1959); she then resigned as president in 1960, focusing her efforts on directing the company’s design and development.

First National Bank of Miami. In 1957, the Knoll Planning Unit began work with the First National Bank of Miami. Florence married the bank’s head, Harry Hood Bassett, the following year. Courtesy of Knoll, Inc.

First National Bank Penthouse Lounge. Courtesy of Knoll, Inc.

While at Knoll, Florence established the Knoll Planning Unit, something that would define the standard for corporate interiors in post-war America. With her architectural background, she applied novel ideas such as efficiency and space planning to the concept of the modern office, favouring open, uncluttered spaces and furniture grouped informally, in a conversational manner. Her work was methodical, rigorously tested and researched. Florence asserted that ‘she did not merely decorate space—she created it.’ This declaration may have been a form of defence, given she was a female designer in what was mainly a ‘man’s world’. As if proving her worth, Florence Knoll and the Knoll Planning Unit created successful interiors for a number of America’s corporate giants, including IBM, General Motors, Heinz and CBS.

In a room filled with men. A Planning Unit meeting in 1953. Florence Knoll is in the foreground with Hans Knoll to her right. Courtesy of Knoll, Inc.

Interior design of the new CBS Building. Courtesy of Knoll, Inc.

The lounge at the Connecticut General Life Insurance Company headquarters. The project represented an opportunity to showcase the fundamental design principles and abilities of the Planning Unit. Courtesy of Knoll, Inc.

With her foresight and vision, Florence Knoll collaborated with notable design contemporaries; these individuals created some of the twentieth century’s most iconic furniture pieces for Knoll: from Eero Saarinen’s Dining Table, Womb Chair and Tulip Chair to Isamu Noguchi’s Cyclone™ Dining Table and Harry Bertoia’s Wire furniture. Moreover, with her network of friends and mentors, Florence acquired the rights to some of their artistic creations, paying them commissions and royalties. Perhaps most famous is Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona Chair—designed in 1929, Mies granted Knoll the production rights to the Barcelona Chair in 1953. It has been in production ever since.

Eero Saarinen’s Saarinen Table, Tulip Armless Chair and Tulip Arm Chair. Courtesy of Knoll, Inc.

Saarinen Womb Chair and Ottoman. Courtesy of Knoll, Inc.

Mies van der Rohe Barcelona Chair. Courtesy of Knoll, Inc.

Many of Florence Knoll’s own furniture pieces are truly iconic mid-century designs—even though she referred to them as the ‘meat and potatoes’—especially the winsome Florence Knoll Hairpin™ Stacking Table and the truly impressive Florence Knoll Table Desk.

Florence Knoll Hairpin™ Stacking Side Table. Courtesy of Knoll, Inc.

Florence Knoll Table Desk pictured with the Saarinen Tulip Arm Chair. Photo by Dean van Dis. Courtesy of Knoll, Inc.

Florence retired in 1965, but occasionally rekindled her relationship with Knoll, including work on legacy projects related to the company. In The New York Times obituary to Florence, Francis Mateo wrote: ‘To connoisseurs of Modernism, the mid-20th-century designs of Florence Knoll, as she was known, were — and still are — the essence of the genre’s clean, functional forms. Transcending design fads, they are still influential, still contemporary, still common in offices, homes and public spaces, still found in dealers’ showrooms and represented in museum collections.’ It is this familiarity with and attachment to her work, this respect and admiration for such a gifted designer, that ensures Florence Knoll Bassett will continue to influence and excite today’s design aficionados and those in generations to come.