Ramón Esteve founded his eponymous studio in 1991, with the confidence and conviction that architecture was a global discipline. Since then, both he and his team have worked to generate design solutions that encompass unique spaces, objects and brands. For Esteve, architecture and design are complementary disciplines, each one enriching the other.

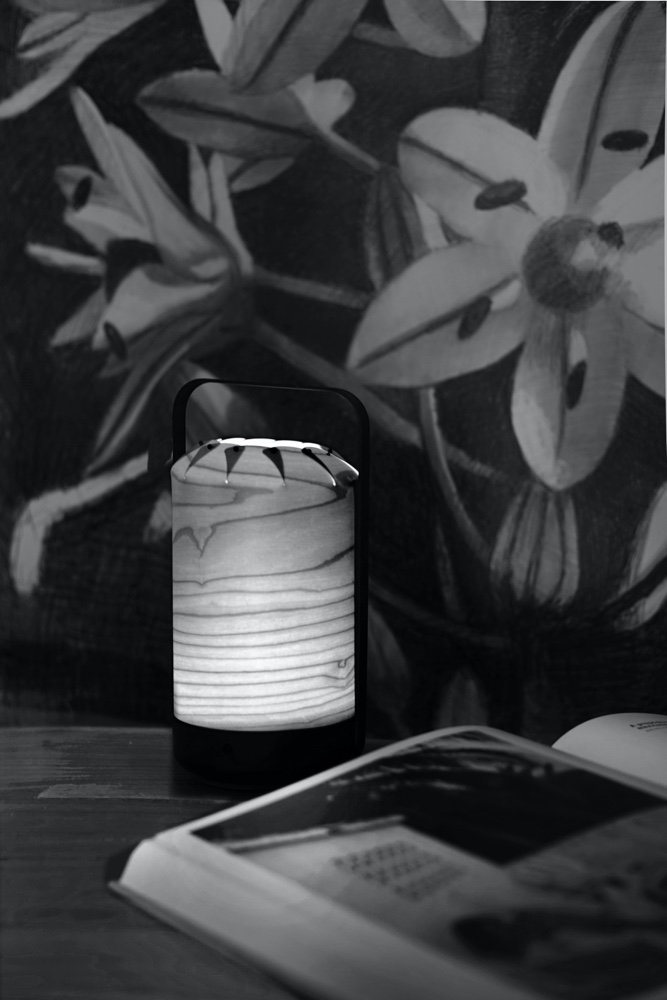

In his approach to design, Ramón Esteve searches for a number of constants, including atmosphere, universality and contextualisation of culture, place and the physical environment. With this in mind, he has designed Black Note, a singular space for LZF at Casa Decor in Madrid. The rather mysterious name draws its inspiration from the black keys on a piano, which are the keys that add emotion and passion to a melody. This also reflects the sensations that LZF wishes to express through its new collections and collaborations. Imagined as a hotel lobby, Black Note is presented as the preamble of an experience that will surprise visitors and change their perception of reality. The space seeks to generate particular feelings by playing with texture, light and colour. Finishes in black and anthracite tones contrast with the luminous, warm white of LZF’s wood veneer lamps. This gives rise to a theatrical atmosphere that also encompasses a sense of freshness and informality. A neon Black Note sign adds a dramatic finishing touch.

Black Note and Mini Chou lamps in Ramón Esteve’s Black Note space at Casa Decor.

The presentation of LZF’s Black Note space at Casa Decor coincides with a preview of the lighting collection of the same name. The Black Note collection, designed by Ramón Esteve, will officially launch at the forthcoming Euroluce exhibition in Milan, during Milan Design Week. Esteve will also design LZF’s Euroluce booth, one that is certain to capture the imagination.

Check out this short video on Black Note at Casa Decor by Alfonso Caza.

An interview with Ramón Esteve

Gerard McGuickin talked with Ramón Esteve to find out more about his relationship with LZF and his work generally.

Architect and designer Ramón Esteve. Image © Alfonso Calza.

What is your relationship with LZF? What does LZF mean to you?

We have known each other for twenty-four years, our respective developmental trajectories corresponding over time—LZF as a brand and I myself as a designer. In fact, it was twenty-four years ago that we each had our first exhibition at Feria Valencia.

LZF has always been a reference for me, because of the brand’s strong identity and the coherence it conveys across its work. Having said that, our professional relationship is quite a recent one and coincides with a moment of change and revision to LZF’s company strategy. In my case, the relationship goes beyond a mere collaboration in terms of product design, and includes creating concepts for the spaces that will project LZF’s image in fairs such as Casa Decor and Salone del Mobile. For me, they are very exciting projects to be involved with.

You are designing new lighting collections for LZF and will design the brand’s booth for Euroluce at this year’s Salone del Mobile in Milan. What can we expect to see?

As I mentioned, LZF is in a moment of change and renewal, although the brand is maintaining those same core values that underpin its great personality. Consequently, at Euroluce we will see a new approach to LZF’s exhibition, one that considers its strategic plan—we will place an emphasis on the new collections and their finishes, presented in a functional space with fluid routes. In terms of aesthetics, we will use some architectural resources with the intention of visually impacting the visitor

When you undertake a new project—such as the space at Casa Decor—what are you particularly curious about? Do you always have an endpoint in mind or does this evolve with time?

When we start a project, we always begin with a basic idea—as we work on the project, it evolves until it has a soul. Sometimes this is achieved straight away, but other times it costs a little more than the project has life. In the case of the Black Note space we designed for Casa Decor, we were clear that we wanted to generate a powerful concept that would lead to an experience that conveys LZF’s strategic development and renewal.

Spain’s design scene is compelling, rich and vibrant, but I often wonder how well it translates on a world stage (competing with Nordic, Japanese, Italian and American design for example). What are your thoughts on Spanish design and its place in a wider design sphere?

As with Italian design, in 1950s Spain, architects started with the roots of vernacular architecture and Mediterranean objects. We have many interesting proposals from that era that have much to do with modernity and tradition, but I would say that Spanish design has probably had less continuity—it has not been supported with the same fervour as in Italy, the USA or Scandinavia. Validation of this is seen in the fact that designers and firms from the 1950s and 1960s continue to have a strong presence in these countries. This is much less so in Spain. That said, I think our design culture is so strong that it has resurfaced over time. Valencia is a great example, having recently announced its campaign for World Design Capital 2022.

In short, Spain has a great differentiation: from the 1930s with GATEPAC (a group of architects assembled during the Second Spanish Republic), until the 1950s and 1960s when several relevant architects from Barcelona and Madrid began to design furniture, and interesting pieces emerged. In my opinion, the key difference between Spain and the countries previously mentioned is the lack of continuity in the companies making these good pieces, meaning we see fewer Spanish design icons at an international level.

‘Manufacturing the Interior’—an excellent design resource on your website—aims to analyse the interaction between furniture and architecture. Can you say a little bit more about that interaction and what it means to you?

Since my beginnings as a designer, I have focused on architecture and design as a global concept, generated under the same laws and the same conceptual premises, with the aim of creating universes, atmospheres and experiences. As such, I could think of no better topic on which to base my doctoral thesis.

I think this approach does nothing but add value to the result—I find it very interesting and enriching to move across different scales and project ranges. This gives the ability, when designing something small, to solve it while at the same time thinking it will be a part of something big. Conversely, when working on a larger project, you can be aware of the importance of having the least detail when it comes to living in that space.