Throughout the twentieth century, the fields of architecture and design were very much the preserve of men, a result of the dominant ideology of patriarchy. Women were all too often sidelined, their contributions and achievements typically downplayed. Unlike the accolades and praise showered upon their male counterparts, many famous and successful female architects and designers were overlooked and undervalued: Aino Aalto, Eileen Gray, Anna Castelli Ferrieri, and Ray Eames, to name but a few design heroines.

Today, we find that many women in architectural, design and manufacturing professions, still contend with the dominance of patriarchy. Women are often less visible than men, less inclined to blow their own trumpet, and more likely to face hurdles in their career progression. In order to address the prevailing status quo, the Women in Office Design (WOD) movement was established, an initiative that prioritises networking opportunities for women (across design broadly). Founded by Harsha Kotak, a London-based interior designer, WOD has flourished and welcomes members from across the world. In Spain, it is led by Gracia Cardona, Director of Diario Design. Here, in our people with character series, we talk with Gracia about Women in Office Design.

Gracia Cardona.

Compared to men, women in the workplace are perhaps less inclined to blow their own trumpet. Why do you think this is?

(GC) In the workplace, women have tended to behave in a more modest manner for a number of reasons, but they can be summarised into just one: our priorities. Our priorities are enforced by the demands of society and often by women themselves. We thought it was ‘bad’ to be professionally visible, since it was a sign of neglecting what is really expected of us—caring for others. To be visible professionally can be misconstrued as being selfish, as opposed to being talented.

What are the key hurdles that women face when they seek to develop and progress in design, architecture and manufacturing roles?

(GC) Curiously, women have dedicated themselves to design and architecture in more creative roles; they have been better received in these disciplines than in other specialisms. Yet, women are often viewed as creative talent ‘in the shade’—they do not access positions of responsibility or seek higher visibility. For example, the great architects who typically handle large budgets have been/are men.

Design heroine Aino Aalto. Photo by Kolmio © Artek.

What are some of the benefits for women of Women in Office Design, a network focused solely on women?

(GC) One immediate benefit of a network for women is that we can talk without imposture—without pretending to be like men. It is a matter of comfort; in conversation, there is the feeling of belonging to a group with many similar concerns. Women feel more relaxed talking with each other, and there is a sense of closeness. Hopefully one day, it won’t have to be like this.

Another benefit for women in a network, and for younger women in particular, is having access to experienced role models and mentors, especially when addressing an issue such as visibility in the workplace. The idea that there are other talented women you want to look like is a powerful one—humans learn a great deal from the examples of others.

Design heroine Eileen Gray (in her later years). Image © NMI.

Historically, the role of women in architecture, design and manufacturing has been grossly underrepresented. How do women, and men, challenge the dominant ideology of patriarchy, still prevalent across these sectors?

(GC) Women are facing up to the ideology of patriarchy by making themselves known, saying ‘here I am’ and ‘I am also valid’. Professionally, I think it is more an evolution than a revolution, with signs of women wanting to participate in decision-making and in positions of responsibility. In other professional areas, such as in politics or justice, the changes are more immediate, more revolutionary.

Men have mostly taken on the role of passive observers. But real change will happen when men are more active as drivers of change, recognising that talent comes before gender, and that a woman is equally capable of performing any task. This is perhaps somewhat easier in the design and architecture sector than in other sectors, although there is still a way to go.

Design heroine Anna Castelli Ferrieri. Photo © Kartell.

‘But where are the women designers, architects, manufacturers… ?’ is one constant refrain. How do you combat this popular misconception?

(GC) Women are in design schools, in studios, in big architecture firms, but often doing the ‘invisible’ work. For me it is more a problem of visibility—not that woman do not exist in these places. That is the objective of WOD: to make visible and celebrate the existence of those women professionals who feel they are not able, or find it difficult, to be visible.

How can WOD work to promote the visibility and inclusivity of black, asian and minority ethnic women, lesbian, bisexual and trans women, and disabled women?

(GC) We do not seek to solve the world’s problems. But if you support the idea of inclusiveness—the idea that everyone is valid—it is a powerful concept that will succeed when it finds acceptance in all areas of society. WOD was born with this philosophy.

Design heroine Ray Eames. Photo © Pat Kirkham via Pioneering Women of American Architecture.

Will a women’s networking movement alone be enough to change things for the better (across architecture, design and manufacturing)?

(GC) Of course it is not enough, but the network is another means of support for many people and institutions throughout society. Normalising the very reality of professional women is a great step: talented women should have the same opportunities as men.

What are some of the highlights and lessons you have taken from the WOD events you’ve attended to date?

(GC) There is a great need in Spain for this type of association. We have noticed that many women want to have more professional support, to explain who they are and what they do, but generally they don’t know how or where to look. WOD is an exciting initiative, not only for women, but also for the many companies who are willing to support it. And we like it this way—WOD wants to be an inclusive partnership with men of course. Inclusive and exciting.

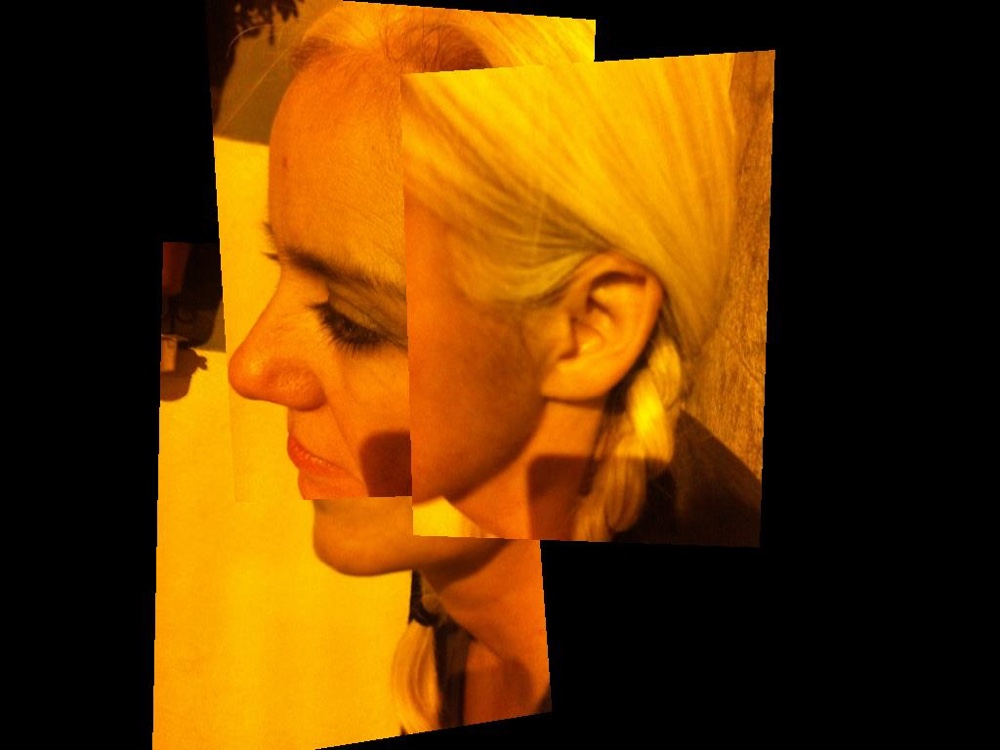

Hard at work. Mariví Calvo, LZF’s co-founder, creative director and very own design heroine.